For such a simple activity, runners excel in getting injured or sidelined from training due to pain. In many cases, simple changes could have averted the problem. As a physical therapist who’s made a career out of migrating runners out of the medical system and towards running enlightenment, I’ve come to appreciate the common denominators that exist among runners who enjoy consistent and healthy training, which is where the magic lies.

Over the years, I’ve distilled the seven most common mistakes I see runners make, and developed a practical fix for each to ensure you stay on the right side of the pain and injury fence.

Top Seven Running Mistakes

- Inconsistent Training

- Relying on Mileage and Pace

- Running Too Fast Too Often

- Not Listening To Your Body

- Poor Decision-Making About Pain

- Skipping Warm-ups & Cool-downs

- Relying Solely on Bodyweight Strength Training

Mistake #1: Inconsistent training

Sporadic or inconsistent running is one of the top reasons runners land themselves under my physical therapy care. Often, when I talk to recreational distance runners about their training schedule, they report running twice a week on average. While there are documented health benefits from running at such a limited frequency, your bones, muscles, and tendons won’t adapt and develop the capacity to withstand the demands of distance running. Each run presents new stress—you’re essentially starting from zero again—which can increase your risk of injury, especially if you do not adopt a sensible pacing strategy or go out for an overzealous long run.

Another scenario that lands runners in my office is when they suddenly go from running two days a week to five or six as part of a New Year’s resolution or after signing up for a race. Doing so creates a spike in their workload and can set the stage for pain or injury by exceeding your current capacity.

How to Fix

A simple recommendation for recreational distance runners looking for fitness and mental health benefits is to run a minimum of three or four times per week on non-consecutive days while engaging in light aerobic activity (e.g., walking or spinning) and/or strength training on non-running days. Not only will this allow your body to adapt, but you’ll also ensure adequate recovery and feel more prepared and fresh heading into each run.

If you are ramping up for a race and looking to increase your running volume, a sensible approach is to first add one more run at a conversational pace (four out of 10 on a scale of effort) to your weekly training schedule. As you look to advance your training, I advise runners to focus on frequency, duration, and intensity (F.D.I.) in that order. Before you extend your long run or increase the intensity of your runs, start by adding another run to your weekly schedule and let your body adapt to the increased volume to prevent overloading and injury.

Mistake #2: Basing Your Runs Solely on Mileage and Pace

Most runners plan their runs based on mileage and pace, as in “Today, I’m headed out for an 8-mile run at 7:30 pace.” While it may seem trivial how you measure your runs, research is starting to question such an approach for three main reasons:

- It doesn’t consider how a runner feels, which can be influenced by several factors including sleep, recovery, hydration, energy, motivation to train, menstrual function, and “life load.”

- It risks glorifying high-mileage or volume-based programs, which may or may not be in your best interest, depending on your age, ability, running experience, goal(s), and/or health status.

- It may underestimate the toll a workout takes on your body, thus increasing the risk of injury.

How to Fix

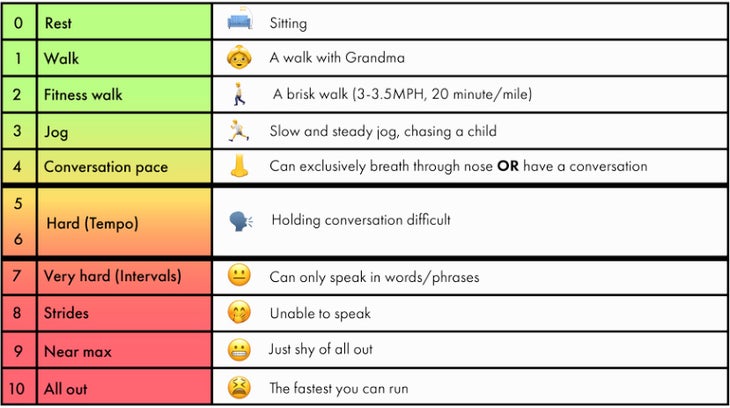

Plan your runs using duration (time running) and rating of perceived exertion (RPE) instead of mileage and pace. For example, rather than run “X” miles at “Y” pace, structure your runs as in “Today I will run for 45 minutes at 4/10 RPE.” RPE is a scale, from 0 to 10, of how hard it feels you are working, with 0 being at rest and 10 an all-out race effort.

Not only will you find your runs more enjoyable, because you’re adapting your effort rather than trying to match a prescribed pace, but you can more accurately track each session’s training load by multiplying the run duration by the session RPE. For example, if you complete a 50-minute run at an average RPE of 4/10, that would result in 200 arbitrary units (A.U.)…yes that’s what they’re called.

While these units are too arbitrary to tell your co-worker—or even a training partner—how much you’re running (“I average 1000 AU’s per week,” doesn’t communicate much), they are much better at quantifying the stress of each workout and ensuring you don’t get injury-producing spikes in your training. Additionally, if you feel sore, tired, or stressed on a day you’re scheduled to run, using RPE instead of pace will help slow you down and ensure you run within your means.

The other benefit of using RPE to guide the intensity of your runs is that different effort levels correlate to heart rate and lactate concentrations, which are often used to distinguish between different training zones. This RPE chart will help you better conceptualize training intensity at each level:

Mistake #3: Running Too Fast Too Often

If there’s one thing I’ve learned over my career as a clinician, coach and runner, consistency and moderation reign supreme when it comes to becoming a robust and efficient runner. Unfortunately, most runners spend far too much time running faster than they should and are too beat up afterward to run again in a day or two, or fail to recover adequately before running again, setting the stage for injury. Anything that threatens consistent running should be avoided at all costs. If you aren’t training consistently, zero physiologic adaptations will occur.

How to Fix

Most successful distance runners do the crux of their training at relatively low intensities. Perform most of your training at a conversational pace or around three to four out of 10 on the RPE scale. Embrace the adage “slow and steady wins the race,” especially if you are new to running or tend to be afflicted by injury.

A wooden pencil is a great metaphor to help you better understand a sensible approach to managing your training intensity distribution. The yellow barrel represents the volume (roughly 80 percent) of lower-intensity running you should typically do. The exposed wood loosely corresponds to the amount of tempo or threshold work, while the graphite tip symbolizes high-intensity work (strides, intervals, fartleks).

Initially, your goal should be to focus on the barrel of the pencil. Once you settle into a rhythm and have been training consistently for several weeks, only then should you consider intensity; otherwise, you run the risk of injury. Assuming you’ve been tolerating the workloads and are looking to get faster, start with no more than one to two “hot sessions” a week. Hot sessions generally take the form of strides, intervals, tempo sessions, and long runs. Essentially, any running that requires a higher than normal state of readiness or freshness going into the workout or more recovery following the session.

Mistake #4: Not Listening To Your Body

As an athlete, it’s perfectly normal to feel like you’re firing on all cylinders one day and flat the next. As noted earlier, daily fluctuations in your performance are expected for various reasons related both to training loads and stresses outside of your running. Too many runners follow a planned schedule religiously or gut out workouts regardless of what their bodies are telling them, and too often this leads to injury.

How to Fix It

Your training should ideally mirror your current fitness, schedule, and life stress to optimize adaptations and safeguard against overtraining and injury. In technical jargon, this is known as “autoregulatory” training. Legendary scientist and biomechanist Mel Siff popularized this form of planning, which adjusts to your day-to-day or week-to-week training based on an assessment of your performance. Autoregulatory training goes hand in hand with RPE, and improves consistency. Research shows it gives athletes greater decision-making authority by allowing them to self-select training sessions based on their perceived capability at the time. As a result, runners are more likely to enjoy training and stick to the program or plan.

Remember that your training will never be picture-perfect, and it’s about the collective body of work, not one day’s workout. The desired physiological adaptations are bound to occur if you train consistently and sensibly while embracing autoregulatory principles. Using a traffic light as a metaphor is the easiest way to apply an autoregulatory approach to your training.

🟢 GO: If you feel rested, energetic, and motivated, it’s a green light day. A safe time to push, but don’t get greedy by overdoing it.

🟡 BE SENSIBLE: If you feel tired, stressed, sore, sluggish, low energy, or unmotivated, treat the situation as a yellow light day. Consider adjusting your workout by shortening your run, reducing the intensity, and nixing any prescribed intervals.

🔴 RETREAT: If you feel exhausted, are coming off a poor night’s sleep, or recently experienced an adverse event (such as losing a loved one), consider skipping the workout or substituting a walk for your training.

Mistake #5: Poor Decision-Making About Pain

Runners tend to make bad decisions in and around pain out of desperation or zeal to run. Chances are, at some point during your running journey, you’ve landed in the pain cave and freaked out over whether you’ll ever return to running and regain your form. The good news is most running-related injuries are overuse in nature and respond to conservative management in the form of activity modifications (stop or reduce running), progressive loading, and reintroducing running in a gradual manner. But some pains shouldn’t be ignored and require professional help.

How to Fix It

Keep these running pain ground rules in mind:

- Experiencing pain around running is not uncommon.

- Avoid running in the context of altered form or mechanics—i.e., you’re limping—unless you are racing and see the finish line in the distance.

- Stop running if your pain worsens to a “disconcerting” or “unacceptable” level.

- If your pain reduces after warming up and remains stable it’s generally safe to train through, provided it returns to baseline within 24 to 36 hours. Be sensible and prioritize lower-intensity training while the pain persists as a general rule of thumb.

- If the pain you’re experiencing prevents you from resting or sleeping, strongly consider seeking medical consultation.

- Pain over bony regions suspected of having stress fractures (e.g., shins and metatarsals) almost always requires cessation of running and medical consultation, especially if you have a history of bone injuries and are experiencing pain with walking.

Mistake #6: Not Including Warm-Ups & Cool Downs

A common denominator among world-class athletes and those who enjoy a career of consistent and healthy training is a systematic, patient, and deliberate warm-up (and cool-down) routine. Unfortunately, as any time-pressed runner knows, the warm-up and cool-down are the first things to fall by the wayside. Skipping the warm-up puts the body under undue stress.

How to Fix

An active or dynamic warm-up essentially boils down to light movement that preps your brain and body as you transition from sedentary to more vigorous activity. Nothing fancy!

At rest, your body allocates most of its circulation to the brain, nervous system, organs, glands, intestines, and other systems. As you go from rest to more intense movement or training, your muscles demand increased blood circulation, given the requirement for oxygen and other nutrients. This process subjects your bodily systems to distress, especially if rushed.

In addition to gradually elevating your body temperature, a warm-up allows you to shift your focus away from the daily grind and towards the impending run. It centers you. By taking the time to perform a gradual warm-up (and cool-down), you can reduce physical stress, safeguard against poor blood pressure response, and potentially mitigate injury.

Most recreational runners should start every run with 10 minutes of walking and end with a five-minute walk. I recommend doing what I call a fitness walk, which involves striding briskly (3.0-3.5mph or 18 to 20 minutes/mile) with arms pumping like running. It elevates your heart rate, promotes blood flow to the working musculature, and allows a nice transition and cognitive shift as you go from sedentary to active. If you feel like your friends would make fun of you if they saw you walking in this manner, you are doing it right. I also like incorporating light skipping and side shuffling (10- to 20-second bouts) into the walking warm-up.

Too many runners needlessly perform various mobility and activation drills when they could go for a walk instead—save the drills to prepare for intense speed workouts when greater muscle activation and range of motion are required. Although you may not feel walking is necessary, I’m confident you’ll start to enjoy and ritualize it as part of your running routine as your runs become more enjoyable and you visit my office less often.

Mistake #7: Relying Solely on Bodyweight Exercises

If there’s one thing a runner should do outside of running and staying on top of wellness factors (i.e., sleep, fueling, etc.), it’s strength training. It’s been fantastic to see more runners incorporating strength work into their overall training plan in recent years. However, many runners tend to rely solely on bodyweight exercises (i.e. squats and planks) and never progress their program beyond simply doing more repetitions.

Although bodyweight exercises afford a slew of advantages and can serve as a great starting point for runners who have limited experience with strength training, their ability to provide the necessary stimulus and overload will be limited in time. So if your goal is to prevent injury while positioning yourself to run further and faster, it’s critical that your strength routine is progressive and focuses on the use of free weights targeting the leg muscles in a standing position.

How to Fix

To run, your muscles must handle high contraction intensity, your tendons must store and release energy, and your bones must withstand high tugging forces from muscles and strain. These forces are often multiples of your body weight. An appropriate resistance training program should therefore prepare you for the performance demands of running while also helping you build a comprehensive capacity to withstand the rigors of life.

- Aim to strength train two times per week, ideally on non-running days. If you have to do it on the same day as a run, feel free to do it directly afterward if it’s a low-intensity run. If it’s a higher-intensity run (tempo, interval, or hill session), ideally, afford four to six hours of recovery to ensure your bones regain their sensitivity to loading.

- Perform a combination of drills in the following order: plyometrics (i.e., pogo jumps or jump rope), compound movements (i.e., squats, deadlifts), single-leg exercises (i.e., step-ups, band-resisted toe taps), and isolation drills (knee extensions, calf raises).

- If you have limited experience with strength training, prioritize heavy slow resistance (HSR) training by performing two to four sets of three to eight repetitions per exercise while using loads corresponding to 70 to 85 percent of a one rep max (RM) range, keeping your total at six to 15 repetitions.

Chris Johnson is a renowned physical therapist, endurance coach, author, and consultant based in Seattle, WA. With over twenty-plus years of experience as a clinician-coach and multi-sport athlete, he helps runners and triathletes overcome pain and injury to achieve their performance goals. Chris combines his extensive knowledge from his research background at the Nicholas Institute of Sports Medicine and Athletic Trauma with his hands-on expertise to guide runners out of the medical system and onto personal bests. Learn more injury-proofing techniques @chrisjohnsonthept